British trivia

Home page

Last update:

27-May-2002

©1996-2007

Mike Todd

| << From the mid 18th century |

Broadcasting

House

Langham Place takes shape

The

19th century

In

1811, Marylebone Park reverted to the Crown, and the Prince Regent employed

architect John Nash to design what was really intended to be one of the

first examples of purpose-built urban planning. There were to be two villages

either side of a fully-landscaped park, all of which in turn was to be

part of a much wider scheme.

In

1811, Marylebone Park reverted to the Crown, and the Prince Regent employed

architect John Nash to design what was really intended to be one of the

first examples of purpose-built urban planning. There were to be two villages

either side of a fully-landscaped park, all of which in turn was to be

part of a much wider scheme.

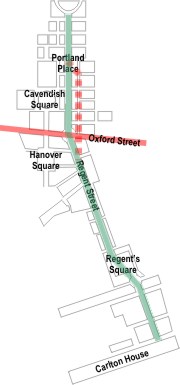

As part of this scheme, Nash had a vision of a magnificent processional route that should run from the Prince Regent's residence at Carlton House (positioned just outside the north end of St James's Park) all the way up to the Regent's summer villa, which was to have been built in the Park.

At about the same time, as luck would have it, Foley's grandson had gambled away the family fortune and Lord Foley went bankrupt. So, in 1814, Foley House (in fact, the entire estate) was sold to Nash to settle the debt. Nash then sold part of the land to Sir James Langham with the agreement that Nash would build Langham's house on part of the site. The remaining land was to be sold to the Crown.

All of this would have allowed Nash's processional route (in green) to pass through Regent's Square (renamed Picadilly Circus in 1880), along Regent's Street and following a route all the way north, past Langham's House (see the 1832 picture below), connecting to the existing Portland Place and up to the Park.

But two things went wrong.

First of all the plan required houses on the block at the eastern side of Cavendish Square to be demolished to make way for this "Regency backbone for London". The residents would have none of this. which meant that Nash had to look at putting the southern extension to Portland Place to the east of this block.

Secondly, Langham had been unhappy with Nash's building of his magnificent town house. Langham dismissed Nash and hired another architect. Intent on exacting some retribution, Nash (who was still the owner of the remaining land at this stage) then announced that he would build new houses right in front of and facing Langham House. Langham was forced to buy up this land, thereby restricting the ability of Nash to extend the processional route up into Portland Place.

This is why there is now a kink in the road (at Langham Place), and why Regent Street south of Oxford Circus bends slight to the east (show in dotted red on the map).

Regent

Street was completed around 1825. The divided Queen Anne Street remained

divided, and the eastern section was named Queen Anne Street East

although it was later renamed Foley Street in memory of the big

house that separated it from its other half.

Regent

Street was completed around 1825. The divided Queen Anne Street remained

divided, and the eastern section was named Queen Anne Street East

although it was later renamed Foley Street in memory of the big

house that separated it from its other half.

As part of this huge development, the government agreed to release some of the land at the north-east of the plot that they had bought from Nash on behalf of the Crown. This was for the building of the Parish Church of All Souls, another building which John Nash was to design. The foundation stone was laid in November, 1822, and the church consecrated two years later.

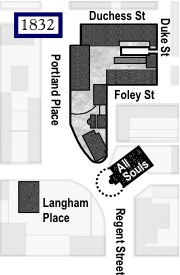

The

map to the right shows the layout in 1832. A small Mews (called Chapel

Mews) runs in from Duke Street, and opposite this (on the site where

now stands Brock House, was St Paul's Chapel).

The

map to the right shows the layout in 1832. A small Mews (called Chapel

Mews) runs in from Duke Street, and opposite this (on the site where

now stands Brock House, was St Paul's Chapel).

But there was one more twist to the story before the land was eventually acquired for building the Langham Hotel.

Langham had taken pity on the Earl of Mansfield, later to become Lord Chancellor, but who was at the time an "impoverished lawyer" from Scotland. Several sources describe a house being built in the middle of the acre of land, and it was Mansfield House that had to be demolished to make way for the Langham Hotel.

The picture below left shows the view up Regents Street, towards All Souls. Straight ahead, just beyond All Souls, at an angle on the "kink" is another "Foley House" which most records show as "8, Portland Place". Just beyond the building on the very left is the open area of Langham Place.

The Langham Hotel Company had been formed to purchase this land (whether from Mansfield or the Langham estate is unclear, but it was not from the Crown as some locals believe, as Nash had sold this part of the poperty to Langham and not to the Crown). The site was considered the "healthiest in London", as it had a very low death rate, and was felt to be perfect for such a prestigous development.

In 1862 they held an architectural competition for the design of the new hotel, and the foundation stone was laid in July, 1863.

Building was expected to take about 15 months, and the opening was planned for March, 1864. However, according to the story told to the Prince of Wales at its opening, concerns over ensuring that the building was suitably fire-proof delayed the opening until June, 1865.

|

|

The new hotel (shown in the picture above right) was one of the biggest buildings in London, and one of the most magnificent hotels in Europe. Costing £300,000 to build, it consisted of 600 rooms, and boasted state-of-the-art fire protection. Water was pumped from a 360ft artesian well into tanks that then fed hose points on every floor. The building had an electric fire alarm system that would alert the four permanently-sited trained fireman to exactly where the fire was located. It was said to be as fireproof as any building could be.

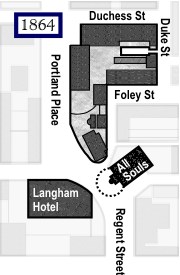

Although

the map on the right shows the layout of the area in 1864, the Hotel was

still being constructed. It opened on 10th June, 1865, claiming to be

the largest building in London.

Although

the map on the right shows the layout of the area in 1864, the Hotel was

still being constructed. It opened on 10th June, 1865, claiming to be

the largest building in London.

Anyone staying at the Langham Hotel was automatically assumed to be of very high standing. Its regular guests included famous names ranging from Napoleon III through to Mark Twain and the hotel had as many as 250 staff on site at a time.

The view down Portland Place was magnificent, with the Langham Hotel dominating the southern end. Houses ran right up to the end of Portland Place, and All Souls Church was just around the corner.

By 1888, Foley Street (which had once been Queen Anne Street, before Lord Foley's house split it in two) was renamed Langham Street ... and so it was, this prestigious area of London entered the 20th century.

| << From the mid 18th century |